Many bloggers have written vividly about the bittersweet process of leaving academia. Yet, the stories are strikingly similar. At a certain point, the pressure, the uncertainty, the long hours, the low-ish wages, and the endless moving from city to city simply become cumulatively unsustainable. One comes to realize that most of these circumstances do not recede if one beats the odds and lands a junior faculty position. For better or for worse, this is the deal. Do you like it or not?

Thinking about leaving

Personally, I feel…worn down by the slow and uncertain grind through the academic ranks. I once overheard an undergraduate researcher ask a junior faculty member about getting into academic science. His reply was simple, “If you can imagine yourself doing anything else, go do that.” At the time I felt his advice to be a bit harsh. Now, I have to say that I get where he was coming from. So I’m going to go do something else. Similar to Lenny Teytelman’s experience of leaving academia, “I feel liberated and happy, and this is a very bad sign for the future of life sciences in the United States.” Given how far this last part is from my locus of control, however, I’m focusing mostly on the “liberated and happy” part :)

The data behind the decision

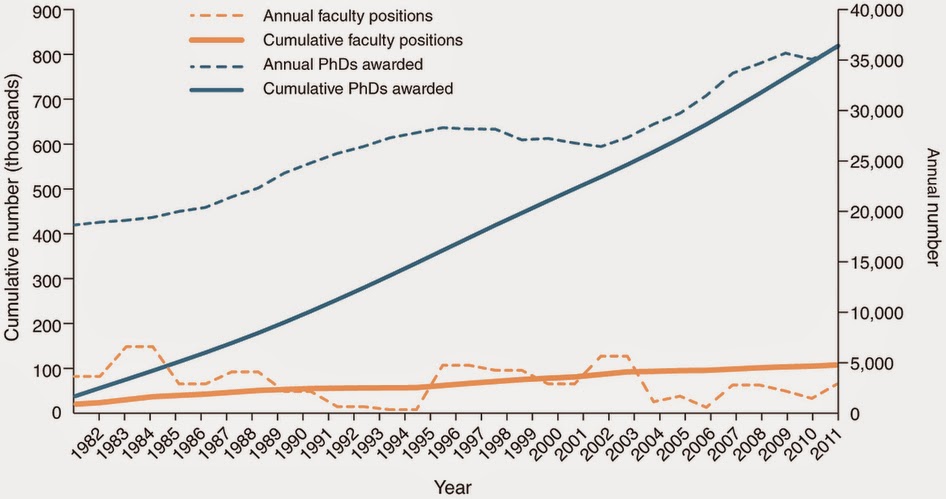

As you can see below, in 2011 there were ~35,000 new PhD graduates, but only about ~3,000 faculty openings. Academic science is overstaffed, and that is leading to unhealthy levels of competition for those who remain. Despite this persistent trend, Francis Collins has stated that he does not believe there is an oversupply of PhDs. This is partly because, even as the situation in academia is becoming increasingly dire, the “unreasonable effectiveness of data” is leading to an explosion of research positions in industries from advertising to biomedicine. In short, we are needed, but mostly not in academia.

Making the leap

The process of leaving academia has been compared to a break up. For me, it’s been a surprisingly emotional decision, especially when people I care about seem to feel let down by my decision. But at the end of the day, I’ve thought this through backwards and forwards, and I know in my bones that it’s right. So I’ve just gotta put on my big boy pants and go for it.

My father also had a shot at becoming a professor, but he too went into industry instead. He took a job at Union Carbide, in part so that he could support my mom and older brother. During his ~30 year tenure at the company, he produced more than 40 patents. He didn’t gain much visibility from his work, but his insights were applied to globally distributed products. Today, you probably can’t go an afternoon without touching something made better or cheaper by his work.

I provide this anecdote a.) because I’m proud of my dad, and b.) to make the point that there are (many) jobs in industry where you can have good career opportunities, solid pay, a high quality of life, and make a real impact. For someone who doesn’t mind being a little picky, I honestly don’t see a downside to taking the leap.

(Unsollicited) advice for graduate students

The staffing situation in science has changed rapidly over the last decade. As a result, conventional wisdom often is not consistent with present circumstances. Graduate students and postdocs need to take an active role in evaluating the situation for themselves, and in demanding greater support in preparing for their most likely career outcomes. Going into industry is not failing or selling out. “Industry” isn’t even really a thing. For many, it’s a catch-all term for “that not-academia stuff I never experienced”. If you wonder what it’s like, go and look up some job postings in your area of expertise. If you find something that looks interesting, considering tailoring your training to better prepare yourself for that type of job.

Background reading

A selection of personal Experiences

Most of this has been rewarding. But in the overly busy mode that most researchers operate in, I found I was feeling less bullish about academia as I knew it and increasingly uncertain it was the right fit…. “If [impact] is my measure for success, [I thought,] “What work must I do to achieve it?” I did some deep thinking and realized that my conservation work—not my academic research—was the work that would help me achieve those lofty goals.

I am now halfway through my 35th year and I have to admit I’m not where I thought I would be…I have come to realize that for a variety of reasons I am unlikely to achieve my lifelong goal of becoming a tenured track professor. I am letting go of some of the… [constant] worrying about the treadmill of the next paper, the next grant, the next position…To get to this place I went through a lot of heartache and depression that closely followed the 7 stages of grief….

I am broke. The System is broke. And this is my story…I put the last eight years of my life on hold, and I’ve set myself up to keep it on hold for the next 5-10 years as a postdoc. But I’m tired of this. I want to go to the movies. I want a dog. I want a family. I want to live my life.

This is the part that worries me the most. We have too many PhDs competing for postdocs. We have too many postdocs competing for fellowships and faculty positions. And we have too many professors, competing for grants. Combined, the low pay, hyper-competition, and the guaranteed uncertainty at every step make the academic track a bad career choice today.

A comprehensive list of “QuitLit”

Quitlit is an entire genre of blog post devoted solely to the experience of leaving academia. Find what other people have written, or contribute your own story here. For convenience, you can also browse below:

A look at the system

- Rescuing Biomedical Research

- Michael Eisen’s take on how to fix things

- PhD Overdrive

- Ailing academia needs culture change